Issue 67: Legume biogeography roundup 2020

Legumes shed new light on the assembly of tropical biomes

Toby Pennington1, Colin Hughes2

1 University of Exeter, U.K. & Royal Botanic Gardens, Edinburgh

2 University of Zurich, Switzerland

Legumes are an ideal group for investigating questions in biogeography from macro to micro scales. The cosmopolitan distribution of the family across almost all major biomes and continents, the high diversity of legume species in many habitats, and their abundance in plant communities mean that legumes can provide a useful proxy for investigating patterns of flowering plant diversity more generally. This prominence of legumes in biogeography is reflected in several notable legume biogeography papers in 2020.

Here, we focus on some key questions in tropical biogeography, but for those with more temperate and subtropical floristic and biogeographic interests, we recommend that you read two papers by Duan et al. (2020) on papilionoid legumes – liquorice (Glycyrrhiza) and the Cladrastis clade. The Cladrastis paper deals with North America – East Asia disjunctions, with suggested migration routes including the boreotropics, North Atlantic and Bering Land Bridges. Glycyrrhiza’s remarkably wide distribution includes temperate South America and Australia, which are suggested to have been reached by long-distance dispersal.

An important question in tropical biogeography is when and how the hyperdiversity of species in rainforests was assembled, and the longstanding debate as to whether rainforests are museums of ancient diversity that accumulated gradually since their early Cenozoic origin, cradles of much more recent and rapid species diversification, or assemblages that result from high episodic species turnover combining both more ancient diversity and recent diversification. Legumes have been central to that debate, and three papers in 2020 provide intriguing new insights.

First, in a phylogenomic study of the Berlinia clade of subfamily Detarioideae, a lineage largely endemic to African rainforests and savannas, de la Estrella et al. (2020) densely sampled the genera Anthonotha + Englerodendron which are almost entirely restricted to African rain forests. What is striking about this study is the recency of the species divergences within the Anthonotha + Englerodendron clade. With crown ages of 2Mya for Anthonotha and 3.4Mya for Englerodendron, the 17 species in each genus diversified almost entirely during the Pleistocene. Another paper this year by Choo et al. (2020) on African and Madagascan detarioid legumes, whilst focusing mostly on issues of evolutionary switches amongst biomes, also infers the ages of African rainforest species of Daniellia. Their diversification started 10Mya, but much speciation is recent – starting in the late Pliocene and continuing into the Pleistocene. This new evidence from Africa mirrors the recency of several Amazonian rainforest clades, suggesting that recent species diversification in rainforests may be a global phenomenon.

Second, new insights into the processes underlying the generation of Amazonian rainforest tree diversity were presented by Schley et al. (2020) in a detailed phylogenetic and population genetic study of the detarioid genus Brownea. Schley et al (2020) presented some of the first evidence that reticulation or hybridisation between both older lineages and extant species has been important in the diversification of tropical rainforest trees. Although hybridisation is undoubtedly a major evolutionary force in temperate floras, a prevailing paradigm, promoted by influential figures in tropical ecology and evolution, including Peter Ashton (1969) and Alywn Gentry (1982), is that hybridisation is rare in tropical trees. One of Schley et al.’s most striking results is the rampant non-monophyly of several widespread species of Brownea, a feature predicted for rain forest species by Pennington & Lavin (2016), and which Schley et al. attribute to reticulation. Overall, they argued that their data suggest that Brownea forms a syngameon, i.e. a widespread species complex in which there is geneflow between sympatric congeneric species. What is clear from all this is that species diversification in rainforests is complex, intricate and still very poorly understood. See also the Kew Science News piece on this study: Taboo trysts between tropical trees.

Two co‐occurring Brownea lineages (Brownea grandiceps (photo © Rowan Schley) and Brownea jaramil-loi (photo © Xavier Cornejo)) and their putative hybrid Brownea “rosada” (photo © J. L. Clark); Figure from Shley et al (2020).

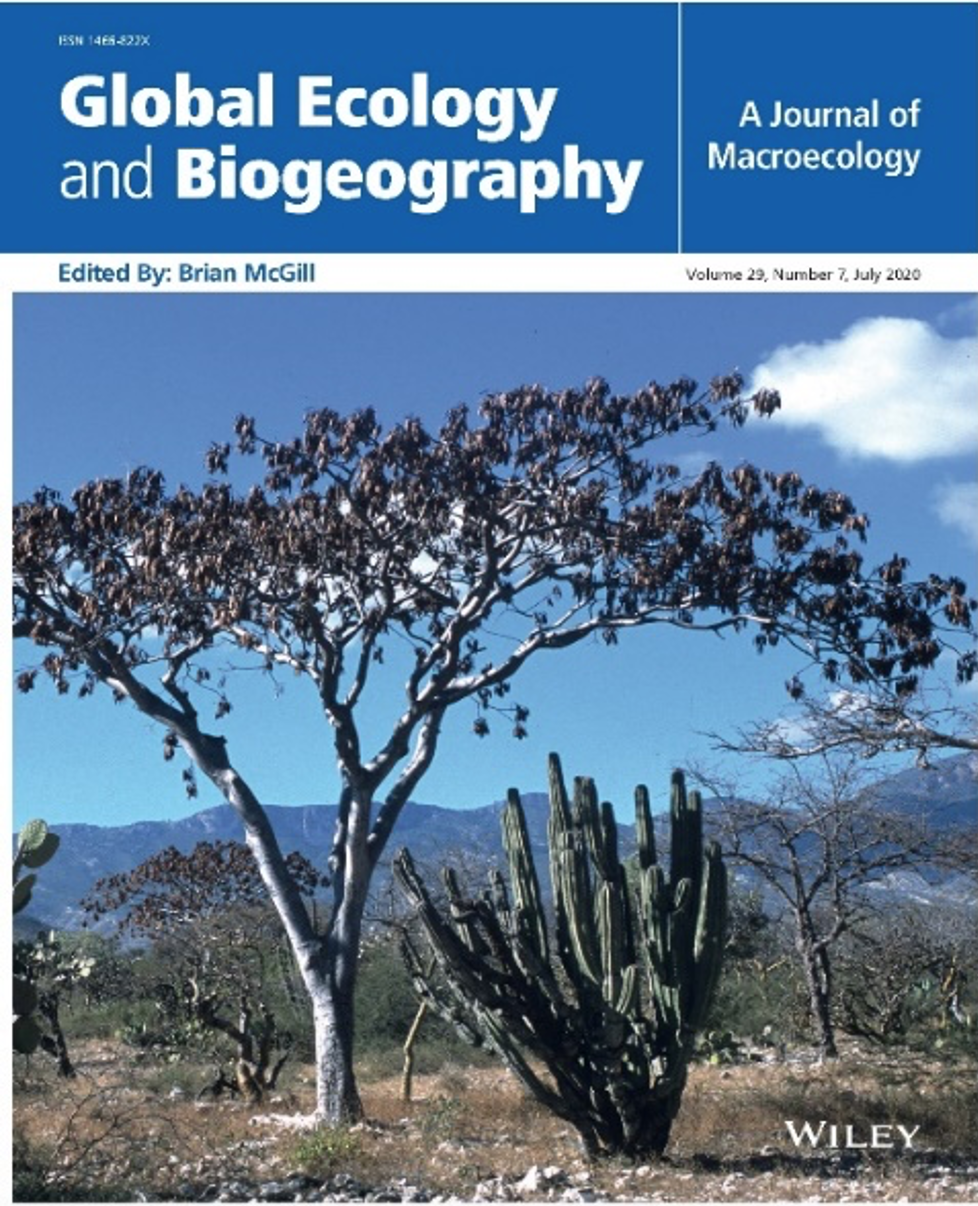

At the other end of the lowland tropical rainfall gradient, legumes have also played a central role in defining the global distribution and understanding the historical assembly of seasonally dry tropical forests. Legumes are often the most species-rich and abundant lineage in these dry vegetation formations, though their most characteristic element is plants with stem-succulence, including cacti and the emblematic baobabs of Africa and Madagascar. It was studies of legume clades that first pointed towards the idea of a trans-continental Succulent Biome (Schrire et al., 2005; Lavin et al., 2004; Gagnon et al. 2019; Donoghue, 2019). In a recent paper, Ringelberg et al. (2020) characterized, modelled and mapped this global succulent biome in detail for the first time by using the distribution of stem succulent species as a proxy and assembled a set of legume (and other) phylogenies to demonstrate high levels of succulent biome phylogenetic conservatism across the transcontinental distribution of this biome. Once again, the prominence of legumes for addressing biogeographical questions comes to the fore.

Typical tropical dry deciduous, grass-poor, fire-free, succulent-rich vegetation in the Tehuacán Valley in central Mexico, part of the trans-continental Succulent Biome which was mapped by Ringelberg et al. (2020). The prominent tree, laden with fruits and leafless during the dry season, is Conzattia multiflora (Leguminosae: Caesalpinioideae), photo Colin Hughes.

References:

Ashton, P. S. 1969. Speciation among tropical forest trees: some deductions in the light of recent evidence. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 1: 155-196

Choo, L.M., Forest, F., Wieringa, J.J., Bruneau, A. and de la Estrella, M. 2020. Phylogeny and biogeography of the Daniellia clade (Leguminosae: Detarioideae), a tropical tree lineage largely threatened in Africa and Madagascar. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 146: p.106752.

de la Estrella, M., Cervantes, S., Janssens, S.B., Forest, F., Hardy, O.J. and Ojeda, D.I. 2020. The impact of rainforest area reduction in the Guineo‐Congolian region on the tempo of diversification and habitat shifts in the Berlinia clade (Leguminosae). Journal of Biogeography 47: 2728-2740.

Donoghue, M. J. 2019. Adaptation meets dispersal: legumes in the land of succulents. New Phytologist 222: 1667–1669.

Duan, L., Harris, A.J., Su, C., Ye, W., Deng, S.W., Fu, L., Wen, J. and Chen, H.F. 2020. A fossil-calibrated phylogeny reveals the biogeographic history of the Cladrastis clade, an amphi-Pacific early-branching group in papilionoid legumes. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 143: 106673.

Duan, L., Harris, A.J., Su, C., Zhang, Z.R., Arslan, E., Ertuğrul, K., Loc, P.K., Hayashi, H., Wen, J. and Chen, H.F. 2020. Chloroplast phylogenomics reveals the intercontinental biogeographic history of the liquorice genus (Leguminosae: Glycyrrhiza). Frontiers in Plant Science 11: 793.

Gagnon, E., Ringelberg, J. J., Bruneau, A., Lewis, G. P., & Hughes, C. E. 2019. Global Succulent Biome phylogenetic conservatism across the pantropical Caesalpinia Group (Leguminosae). New Phytologist 222: 1994–2008.

Gentry, A. H. 1982. Neotropical floristic diversity: Phytogeographical connections between Central and South America, Pleistocene climatic fluctuations, or an accident of the Andean orogeny? Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 69: 557-593.

Lavin, M., Schrire, B. D., Lewis, G.P., Pennington, R. T., Delgado-Salinas, A., Thulin, M., Hughes, C.E., Beyra-Matos, A. and Wojciechowski, M. F. 2004. Metacommunity process rather than continental tectonic history better explains geographically structured phylogenies in legumes. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 359: 1509–1522.

Pennington, R.T. and Lavin, M. 2016. The contrasting nature of woody plant species in different neotropical forest biomes reflects differences in ecological stability. New Phytologist 210: 25-37.

Ringelberg, J.J., Zimmermann, N.E., Weeks, A., Lavin, M. and Hughes, C.E. 2020. Biomes as evolutionary arenas: Convergence and conservatism in the trans‐continental succulent biome. Global Ecology and Biogeography 29: 1100-1113.

Schrire, B. D., Lavin, M., & Lewis, G. P. 2005. Global distribution patterns of the Leguminosae: Insights from recent phylogenies. Biologiske Skrifter 55: 375–422.

Schley, R.J., Pennington, T., Perez-Escobar, O.A., Helmstetter, A.J., de la Estrella, M., Larridon, I., Kikuchi, I.A.B.S., Barraclough, T.G., Forest, F. and Klitgaard, B.B. 2020. Introgression across evolutionary scales suggests reticulation contributes to Amazonian tree diversity. Molecular Ecology 29: 4170-4185.