Issue 67: New insights into the role of polyploidy in legume evolution

Jeff J. Doyle

School of Integrative Plant Science Sections of Plant Biology, Plant Breeding & Genetics, and the L.H. Bailey Hortorium, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA 14853 (jjd5@cornell.edu)

2020 produced a major advance in legume systematics, evolution, and comparative genomics in two papers by Koenen et al. (2020a, b). These studies have propelled legumes into the phylogenomics era, using thousands of genes from the nucleus as well as the chloroplast to provide a dated phylogeny for the family and to explore the implications for legume diversification and evolutionary biology. They are “instant classics”—thorough, detailed, insightful, provocative, scholarly works of the first magnitude—and it is impossible to do full justice to them in the space available here, so I will focus on just one consequential topic for which these papers provide revolutionary information for the family: polyploidy.

Discussions about polyploidy at all levels of legume evolution go back at least to Goldblatt’s 1981 paper on “cytology and phylogeny” in Advances in Legume Systematics Part2. In the early 2000s, correlated divergence times of gene transcripts (Ks peaks) led to the hypothesis of ancient whole genome duplications (WGDs) in the genomes of Medicago and Glycine (Blanc and Wolf 2004; Schlueter et al. 2004), which an early phylogenomic analysis confirmed as being a shared event (Pfeil et al. 2005). A decade later, Cannon et al. (2015) showed that this WGD was present in the ancestor of subfamily Papilionoideae; surprisingly, they also found evidence for three additional independent WGD events: in Copaifera (Detarioideae), Bauhinia (Cercidoideae; but not in Cercis) and in all five Caesalpinioideae (sensu LPWG 2017) sampled. This work was based on gene and taxon sampling from the Thousand Plant Transcriptomes (1KP) project, whose capstone paper (Leebens-Mack et al. 2019) also identified these four legume events among the 244 green plant WGDs. More recently, Stai et al. (2019) hypothesized that Cercidoideae, other than Cercis, is derived from an allopolyploid ancestor formed by hybridization between an unknown diploid species and a diploid ancestor of modern Cercis.

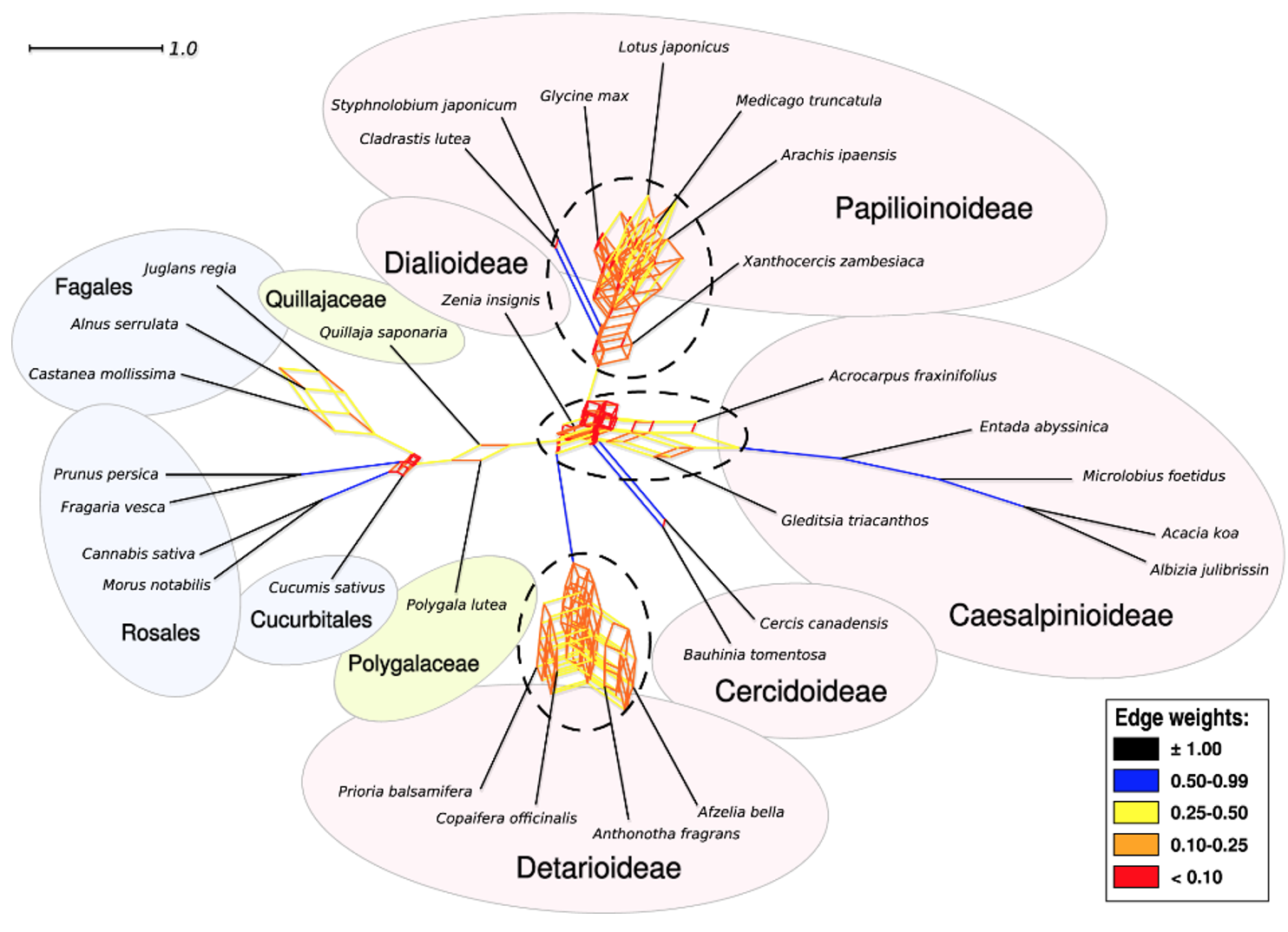

With their much better taxon sampling and the use of several analytical strategies, Koenen et al. (2020b) explored the WGD issue thoroughly, and the first part of the title of their paper captures their conclusions: “The origin of legumes is a complex paleopolyploid phylogenomic tangle.” In contrast to previous conclusions, their results best support three WGD events, with one each in the lineages leading to Papilionoideae and Detarioideae, respectively. The third event, like the papilionoid-specific WGD, occurred very early in legume history, during the rapid radiation of the six subfamilies near the Cretaceous-Paleogene Boundary (KPB; around 66 million years ago). This event may have occurred in the lineage leading to all legumes, or it may have involved hybridization between early ancestors of two extant legume lineages—an allopolyploid reticulate “tangle”.

Figure 3 from Koenen et al. (2020b). Filtered supernetwork of the legumes showing tangles of gene tree relationships at the bases of the legumes, and sub-families Detarioideae and Papilionoideae, that correspond to WGDs, as well as possible reticulation at the base of Caesalpinioideae.

As Koenen et al. (2020b) appropriately note, more work is needed to address this important comparative genomics question, which impinges on many significant evolutionary issues. The results of Koenen et al. (2020a, b) imply that all anatomical, morphological, biochemical, physiological, and ecological characters are underlain by genes that belong to gene families whose membership and expression patterns are shaped by WGDs. Both autoand allopolyploidy are known to generate evolutionary novelty (e.g., Levin 1983; Freeling and Thomas 2006; Doyle and Coate 2019), and hybridity in allopolyploids is associated with heterosis (Washburn and Birchler 2014). To take just one important legume trait, the symbiotic fixation of atmospheric nitrogen, it was suggested that polyploidy could have played a role in either the origin or the refinement of nodulation (Young et al. 2011; Li et al. 2013). Cannon et al. (2015), in reporting additional polyploidy events distributed across both nodulating and non-nodulating legumes, concluded that the relationship between polyploidy and nodulation was too complex for simple generalizations. As Koenen et al. (2020a) noted, there has been renewed debate about the number and placement of nodulation origin and loss in the “Nitrogen Fixing Nodulation Clade” of rosids in which legumes are embedded (van Velzen et al. 2019; Battenberg et al. 2018). Nodulation has been suggested to be responsible for the evolutionary success of legumes, though this, too, remains an open question (Afkhami et al. 2018). And the idea that polyploidy may have facilitated the survival of key plant lineages across the KPB (Fawcett et al. 2009) is an old idea, now refined with new insights for legumes by Koenen et al. (2020b).

How the phylogenetic distribution of nodulation and polyploidy fit separately or together in the context of legume diversification are big questions, and years of exciting work lie ahead. Koenen et al. (2020a, b) have provided an excellent foundation on which to build the next generation of legume systematics and evolutionary genomics.

Afkhami ME, Luke Mahler D, Burns JH, Weber MG, Wojciechowski MF, Sprent J, Strauss SY. 2018. Symbioses with nitrogen-fixing bacteria: Nodulation and phylogenetic data across legume genera. Ecology 99(2): 502.

Legume Phylogeny Working Group, LPWG. 2017. A new subfamily classification of the Leguminosae based on a taxonomically comprehensive phylogeny. TAXON 66(1): 44-77.

Battenberg K, Potter D, Tabuloc CA, Chiu JC, Berry AM. 2018. Comparative transcriptomic analysis of two actinorhizal plants and the legume Medicago truncatula supports the homology of root nodule symbioses and is congruent with a two-step process of evolution in the nitrogen-fixing clade of Angiosperms. Frontiers in Plant Science 9(1256).

Blanc G, Wolfe KH. 2004. Functional divergence of duplicated genes formed by polyploidy during Arabidopsis evolution. Plant Cell 16(7): 1679-1691.

Cannon SB, McKain MR, Harkess A, Nelson MN, Dash S, Deyholos MK, Peng Y, Joyce B, Stewart CN, Jr., Rolf M, et al. 2015. Multiple polyploidy events in the early radiation of nodulating and non-nodulating legumes. Molecular Biology and Evolution 32(1): 193-210.

Doyle JJ, Coate JE. 2019. Polyploidy, the nucleotype, and novelty: The impact of genome doubling on the biology of the cell. International Journal of Plant Sciences 180(1): 1-52.

Fawcett JA, Maere S, Van de Peer Y. 2009. Plants with double genomes might have had a better chance to survive the Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction event. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106(14): 5737-5742.

Freeling M, Thomas BC. 2006. Gene-balanced duplications, like tetraploidy, provide predictable drive to increase morphological complexity. Genome Research 16(7): 805-814.

Goldblatt, P. 1981. Cytology and the phylogeny of Leguminosae. In: Polhill RM, Raven PH (eds). Advances in legume systematics, Part 2. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, pp 427–464

Koenen EJM, Ojeda DI, Steeves R, Migliore J, Bakker FT, Wieringa JJ, Kidner C, Hardy OJ, Pennington RT, Bruneau A, Hughes, CE. 2020a. Large-scale genomic sequence data resolve the deepest divergences in the legume phylogeny and support a near-simultaneous evolutionary origin of all six subfamilies. New Phytologist 225(3): 1355-1369.

Koenen EJM, Ojeda DI, Bakker FT, Wieringa JJ, Kidner C, Hardy OJ, Pennington RT, Herendeen PS, Bruneau A, Hughes CE. 2020b. The origin of the legumes is a complex paleopolyploid phylogenomic tangle closely associated with the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) mass extinction event. Systematic Biology https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syaa041

Leebens-Mack JH, Barker MS, Carpenter EJ, Deyholos MK, Gitzendanner MA, Graham SW, Grosse I, Li Z, Melkonian M, Mirarab S, et al. 2019. One thousand plant transcriptomes and the phylogenomics of green plants. Nature 574: 679-685.

Levin DA. 1983. Polyploidy and novelty in flowering plants. American Naturalist 122(1): 1-25.

Li Q-G, Zhang L, Li C, Dunwell JM, Zhang Y-M. 2013. Comparative genomics suggests that an ancestral polyploidy event leads to enhanced root nodule symbiosis in the Papilionoideae. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30(12): 2602-2611.

Pfeil BE, Schlueter JA, Shoemaker RC, Doyle JJ. 2005. Placing paleopolyploidy in relation to taxon divergence: A phylogenetic analysis in legumes using 39 gene families. Systematic Biology 54(3): 441-454.

Schlueter JA, Dixon P, Granger C, Grant D, Clark L, Doyle JJ, Shoemaker RC. 2004. Mining EST databases to resolve evolutionary events in major crop species. Genome 47(5): 868-876.

Stai JS, Yadav A, Sinou C, Bruneau A, Doyle JJ, Fernandez-Baca D, Cannon SB. 2019. Cercis: A non-polyploid genomic relic within the generally polyploid legume family. Frontiers in Plant Science 10: 345.

van Velzen R, Doyle JJ, Geurts R. 2019. A resurrected scenario: Single gain and massive loss of nitrogen-fixing nodulation. Trends in Plant Science 24(1): 49-57.

Washburn JD, Birchler JA. 2014. Polyploids as a “model system” for the study of heterosis. Plant Reproduction 27(1): 1-5.

Young ND, Debelle F, Oldroyd GED, Geurts R, Cannon SB, Udvardi MK, Benedito VA, Mayer KFX, Gouzy J, Schoof H, et al. 2011. The Medicago genome provides insight into the evolution of rhizobial symbioses. Nature (London) 480(7378): 520-524.